Traveling by car, one would never believe that the Ukrainian government spends Hr 10 billion ($466 million) yearly on road maintenance. Some 97 percent of the nation's 170,000 kilometers of roads are in "unacceptable" condition, according to the Infrastructure Ministry, leading to higher than average road deaths, as well as increased transportation and vehicle insurance costs.

In their current condition, Ukrainian roads need up to Hr 1 trillion in funding over the next 10 years to complete repairs, according to the Infrastructure Ministry. Otherwise, the death toll from road accidents will remain four times the European average, Roman Khmil, head of the road sector strategic development department at the ministry, wrote in the Kyiv Post on May 27.

Meanwhile, trucks can average only 30 kilometers per hour on the country’s crumbling roadways, driving up transportation costs.

But the ministry is looking to bypass Ukravtodor, the state-run agency that many blame for the poor state of roadways, and inefficient – if not corrupt – government spending. Parliament is expected to act on the ministry’s legislation in September when it returns from its summer break.

Ukrainian Infrastructure Minister Andriy Pyvovarsky says he wants to quadruple the roads budget to Hr 40 billion – or $1.87 billion – but through competitive bidding in the private sector. Ukraine’s economy, according to Khmil, can expect to receive $1.60 in return for every $1 invested in roads over the next 5-10 years.

“Ukraine will involve independent contractors and auditors in the construction and examination of roads,” Pyvovarsky promised on Aug. 7.

While Ukravtodor is legally accountable to the Infrastructure Ministry, gaps in legislation have allowed the agency to practically ignore it, according to Pyvovarsky.

Ukravtodor declined to comment on the proposed changes.

“This is completely the Infrastructure Ministry’s idea and we can’t comment on that,” Sergiy Levytsky, Ukravtodor’s spokesperson, told the Kyiv Post on Aug. 13, noting that Sergiy Pidhaynyy, the head of Ukravtodor, was not in Kyiv.

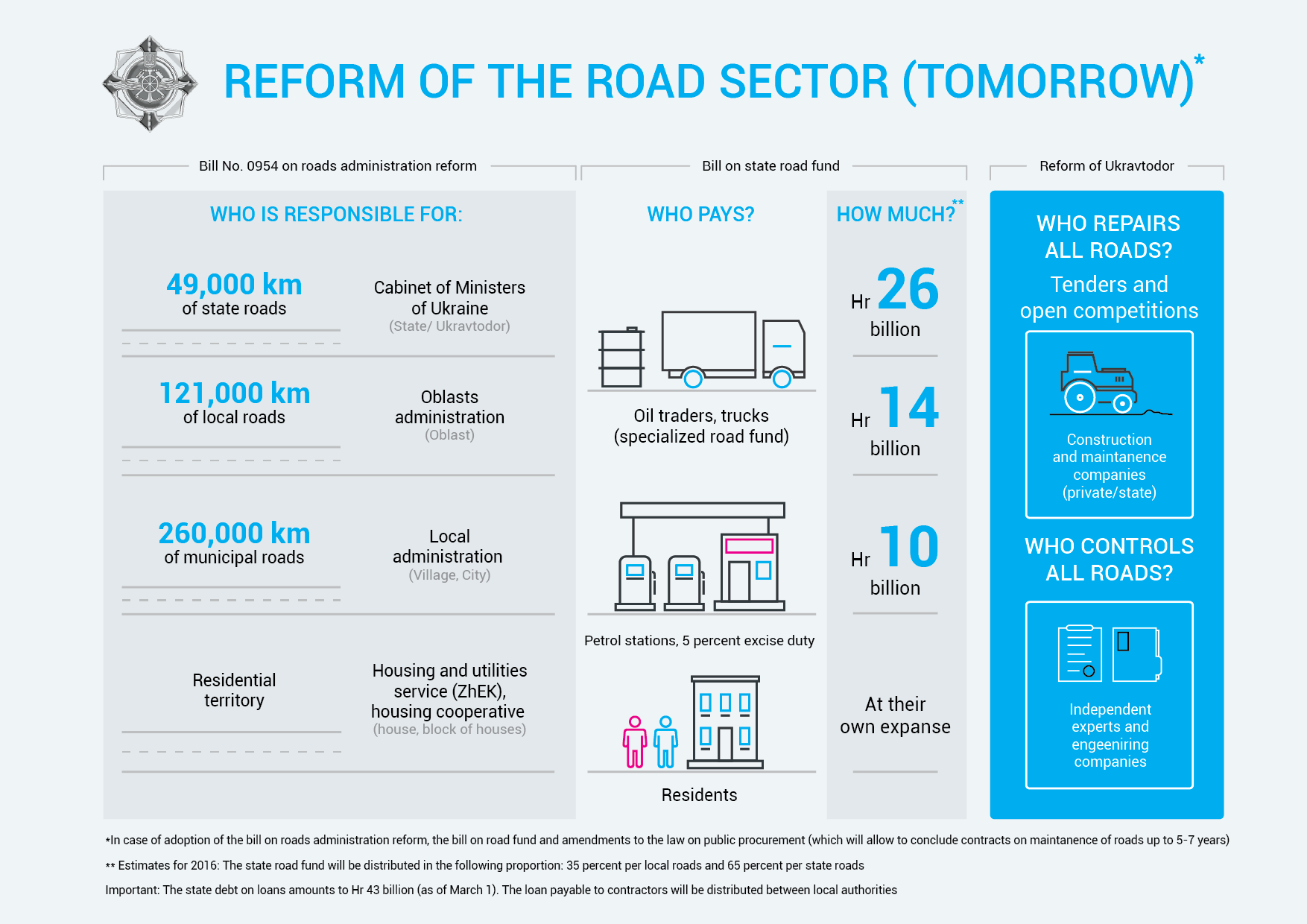

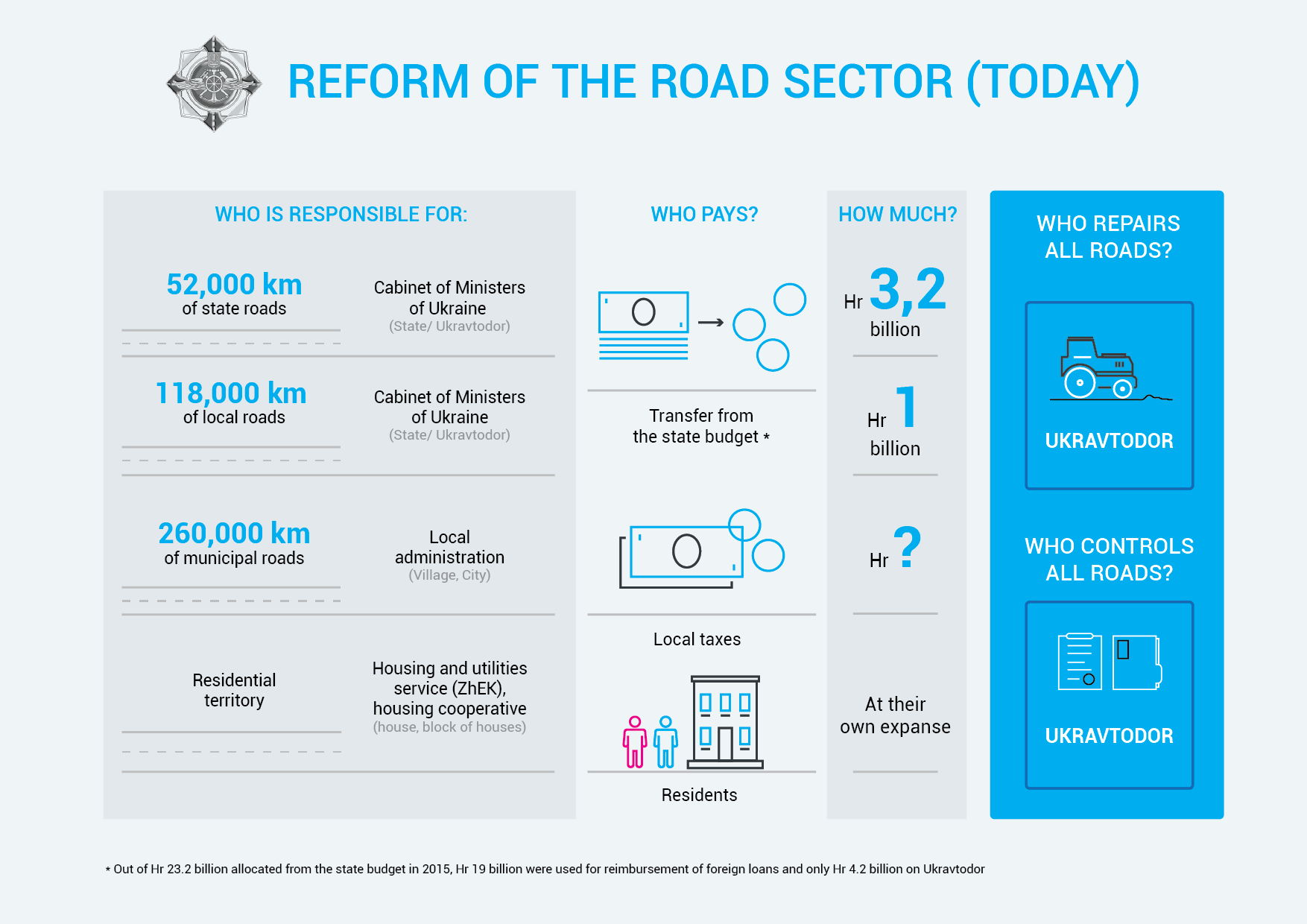

One of the two bills drafted by the ministry draws a clear line between state, regional and local roads and identifies the market’s main players, while another one creates a specialized budget for financing the road network.

If the measures are passed, Ukravtodor will only remain in charge of 29 percent of the nation’s roads. Local governments, in turn, will manage the remaining 381,000 kilometers, with Ukravtodor’s regional branches being transferred to their purview.

Because the road repair industry hasn’t been financed systemically, the practice of simply filling in potholes has become a “post-Soviet phenomenon,” Pyvovarsky said, adding that the practice has replaced other larger-scale repairs.

“For systemic change in this direction we need to change the existing mechanism of road operation and ensure funds are spent properly,” he said.

James Mathews, an international expert on roads with the Austrian engineering company iC consulenten, which recently completed a quality assessment of roads in Kyiv Oblast, says that shifting to capital reconstruction from short-term solutions like patching repairs is the only way to improve the condition of Ukraine’s roads.

“Patching repairs are viable up until they cover 54 percent of the road surface,” Mathews said. “After that, it’s more economically viable just to resurface the (whole) road.”

To raise money, the Infrastructure Ministry wants to create a special fund that will receive money from taxed imported fuel, fees from trucks, and toll roads.

State coffers currently receive about $1.5 billion per year from charging €100 per ton of imported diesel and €200 for petrol, according to Khmil. Only 20-30 percent of that money is spent on roads, while the rest is reallocated to other government spending.

If the ministry manages to get all the collected taxes, it could spend Hr 40 billion over the next year on road repairs.

By comparison, so far only Hr 4.2 billion, a mere 10 percent of the costs needed to pay for road patching, was actually spent on Ukravtodor’s needs this year. The agency used another Hr 19 billion that was budgeted for 2015 to pay back its debts.

But Olga Fayzieva, a lawyer from law firm ENGARDE, says the ministry’s estimates are overly optimistic and can’t be fulfilled without first drafting a detailed budget that specifies short-, middle- and long-term goals for the specialized funding, including how money will be appropriated, responsible personnel, as well as other aspects of the program.

“The proposed bills often overlap, which proves that they (Infrastructure Ministry) lack a systematic approach,” Fayzieva said.

Later this month, the Infrastructure Ministry plans to announce a tender for a centralized audit of all Ukraine’s roads to be conducted, and which is supported by the World Bank.

It will also push for changes in public procurement legislation that would allow private companies to conclude contracts for the exploitation of roads for up to 5-7 years, instead of the one-year term that is in place now.

“Either we switch to an absolutely different system, or we continue fruitless talks on how bad the Ukrainian roads are for the next few years,” Pyvovarsky said.

The infographic explains how the existing system of road maintenance will change if parliament approves legislation that changes the way roads are managed and funded. If adopted, Ukravtodor, Ukraine’s state-run road agency, would lose power and funding to local authorities. The busting of Ukravtodor’s monopoly will also open the way for private investors and independent audits. Source: Ukraine’s Infrastructure Ministry.

Kyiv Post legal affairs reporter Mariana Antonovych can be reached at [email protected].