Prosecutors and judges are both excessively lenient, raising questions about whom they may be protecting. At present, Ukraine has 10,279 judges and 20,367 prosecutors. The almost unanimous popular view is that they are all corrupt.

An example illustrates the corruption in the system: In 2007 a Constitutional Court judge was caught red-handed accepting a bribe of $12 million (officially a “consultancy fee” to her retired mother). President Viktor Yushchenko sacked her, but Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovych reinstated her, claiming that the president had exceeded his legal authority.

Ukraine has an independent High Council of Justice that appoints judges, but several institutions that appoint its members are considered pervasively corrupt, such as those representing judges, lawyers and legal scholars, which each appoint three of its 20 members. Corrupt lawyers and judges should not be allowed to reappoint one another. Institutions that appoint members of the High Council of Justice should be either purged or prevented from appointing judges.

On Oct. 14, the parliament adopted a new law on prosecution, which was an important first step and one of the European Union conditions that Yanukovych refused to fulfill. It sought to reduce the power of the prosecutors to the norm in developed societies. It took away the prosecutors’ general oversight function, which was a Soviet inheritance that rendered them superior to judges. It eliminated their right to interfere in the lives of Ukrainian citizens and businesses. Prosecutors can no longer conduct pretrial investigations, which are now supposed to be handled by a state investigation bureau yet to be created. The qualifications to become a prosecutor are supposed to become rigorous and recruitment transparent. This law amended no fewer than 51 laws and 10 legal codes.

In the preceding week, the Parliament adopted amendments to the Criminal Code and the Criminal Procedural Code to bring to justice the nation’s former leaders, who have fled the country and to confiscate their property. In a next step, Poroshenko signed a decree to form a council for judicial reform.

To accomplish these goals, Ukraine needs assistance, which the European Union, the Council of Europe, Canada or the United States should consider providing.

Initially the High Council of Justice could be made up exclusively of qualified Ukrainian-speaking lawyers, judges and legal scholars fom abroad, for example, Canada, the United States and Europe. They should appoint new judges from the top down, drawing on younger Ukrainian lawyers. After the corps of judges has been built, the High Council of Justice could be composed anew on the lines of the current Constitution.

Anders Aslund is the author of “Ukraine: What went wrong and how to fix it.” The book is published by the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

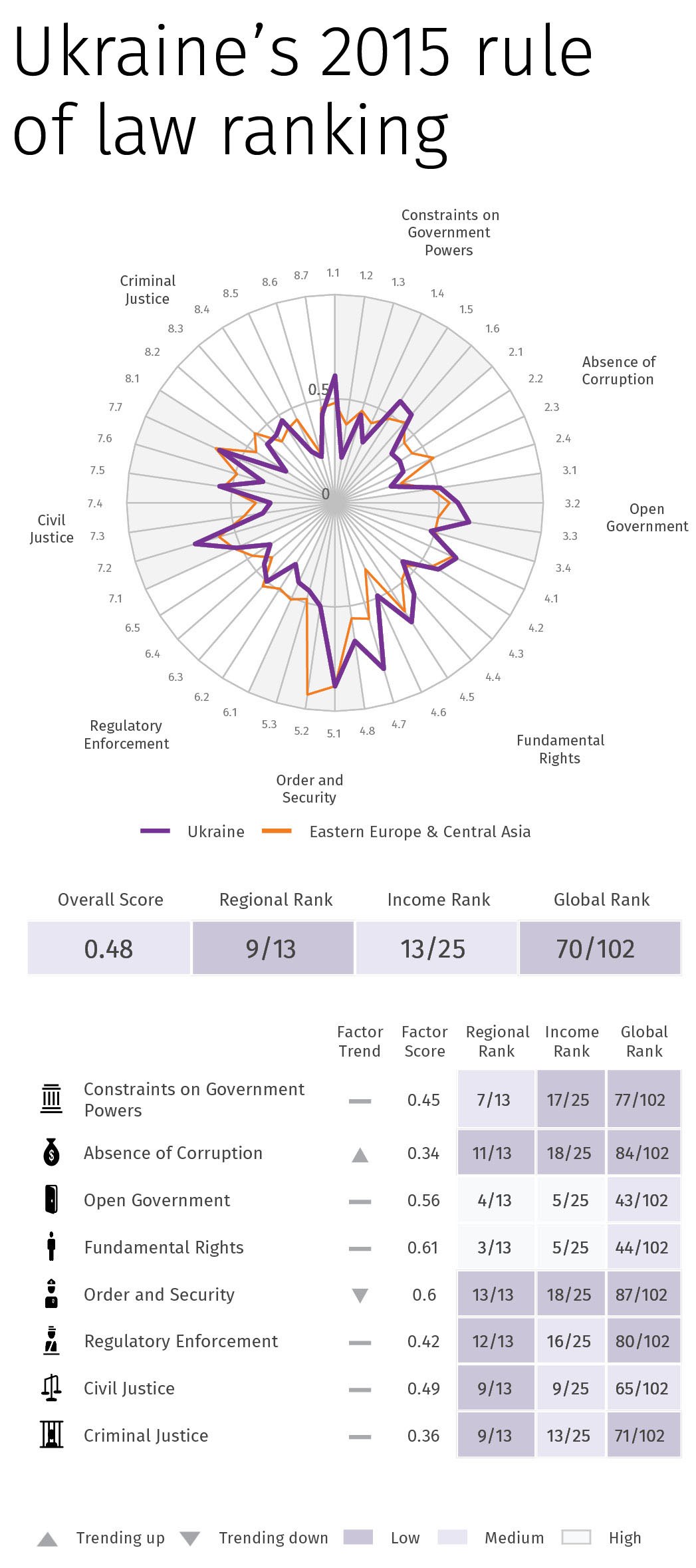

Ukraine’s 2015 rule of law ranking

Ukraine ranks 70th out of 102 nations in rule of law based on eight factors measured in a survey of 1,000 respondents in Kyiv, Kharkiv and Odesa as well as in-country legal practitioners and academics, the U.S.-based World Justice Project found in a study published on June 2. Regionally, Ukraine placed 9th among 13 nations, ahead of only Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Turkey and Uzbekistan. Number 1 indicates the strongest adherence to rule of law, whereas 0 indicates weakest. Ukraine was weakest in absence of corruption (0.34) and criminal justice (0.36), while performing best in fundamental rights (0.61) and order and security (0.6).

Source: World Justice Project