Oligarchic wealth dwindles

Forbes magazine has assessed the net wealth of Ukraine’s oligarchs each March for several years. Only six Ukrainians were ranked by Forbes in both 2012 and 2015. Their total wealth is small by most international standards and so is their number. Presumably, Forbes has not caught all their wealth.

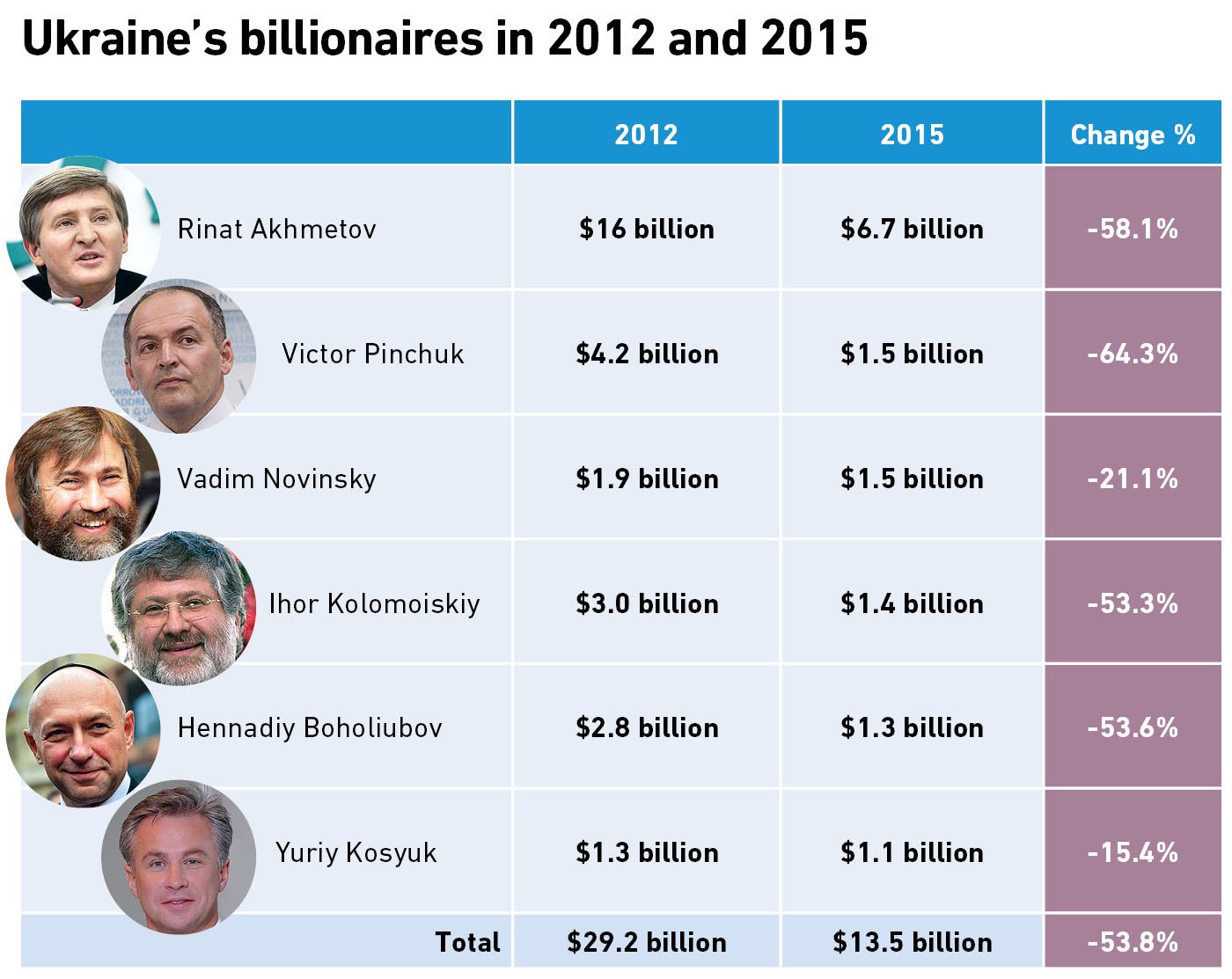

In the last three years, every big Ukrainian businessperson has lost much of his wealth. Forbes assessed that their total net wealth declined by 54 percent from $29 billion in 2012 to $13.5 billion in 2015. The richest, Rinat Akhmetov, has lost more than half of his fortune and he continues to bleed. The Ukrainian economy has shrunk similarly and the oligarchs have been unable to escape these blows.

Many worry about President Petro Poroshenko, but his assets peaked in 2013 at $1.6 billion and he no longer figures on the Forbes list. Gas trader Dmytro Firtash has never made the billionaire’s list; Forbes assesses his net wealth at merely $500 million.

One blow after another

In the last few years, Ukraine’s tycoons have suffered one blow after the other.

When Viktor Yanukovych was elected president in February 2010, most big businesspeople cheered. Many were given cabinet posts and their great boondoggle was discretionary public procurement, giving them attractive state orders without competition. Gazprom and Yanukovych offered Firtash a fortune in gas, which he somehow spent.

The fortunes of the nation’s six richest billionaires, as measured by Forbes magazines, have fallen significantly in the last three years, undercutting their financial and possibly political power as well. Source: Forbes Magazine

After a year, however, Yanukovych had consolidated his power. He finished off the oligarchy, concentrating the fortunes to his family. Allegedly, the Yanukovych family extorted big Ukrainian businesspeople. The young family courtier, Serhiy Kurchenko, claimed a fortune of $3 billion. Yanukovych dealt a severe blow to the old oligarchs. Ukraine’s democratic breakthrough made these people flee to Moscow, and their wealth is dwindling.

In parallel, the global commodity boom came to an end. Steel, iron ore and coal prices plummeted on world markets. These industries are likely to be depressed for years to come, which will hurt the owners of old Soviet industries, notably Akhmetov and Vadim Novinsky.

Russian aggression against Ukraine has hit the oligarchs even harder. In the summer of 2013, Russia started a trade war with Ukraine. One early target was steel pipes, exported to Russia by the pro-European businessmen, Victor Pinchuk of Interpipe and Sergiy Taruta of Industrial Union of Donbas.

The Kremlin blocked their sales to Russia through anti-dumping measures. Another Kremlin target was Poroshenko’s Roshen, whose chocolate was no longer deemed edible by the biased Russian sanitary inspection. The Russian government has also audited Poroshenko’s large confectionary factory in Lipetsk, Russia.

The occupied part of Donbas has been the most oligarchic part of Ukraine with its steelworks, mines, power stations and chemical factories. Russia’s war in the Donbas has cut production. Akhmetov has been hit worst of all. His traditional tactic of trying to be friendly with all sides backfired, rendering him suspect to all.

The same is true of his partner Novinsky. The Alchevsk Metallurgical Combine, the crown jewel of the Industrial Union of Donbas, has stood still since July, and Taruta has lost most of his fortune. Two of Firtash’s big fertilizer factories are in occupied territory and out of work, and he owns the two biggest factories in Crimea as well.

The Kolomoisky drama

Only one big Ukrainian businessman seemed to thrive in the post-Yanukovych regime, Igor Kolomoisky of the informal Privat Group in Dnipropetrovsk. He became governor in Dnipropetrovsk and seemed omnipotent. Wars favor strong men, and Kolomoisky was credited for keeping Dnipropetrovsk peaceful and loyal.

Among Ukraine’s big businesspeople, hardly anybody has a worse reputation than Kolomoisky. His seizure of the company Ukrtatnafta with the Kremenchuk Oil Refinery in 2008 led to a verdict against the Ukrainian state in the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg last year, costing the state more than $100 million in fines because it had failed to uphold property rights laws against Kolomoisky.

For more than a decade, Kolomoisky with partners have controlled the oil-producing company Ukrnafta with only 42 percent of its shares, while the state owns 50 percent plus one share. Ukrnafta has sold its oil at rigged “auctions,” at prices typically only one third of the market price to his fully owned oil companies, while refusing to pay any dividend to the state. Kolomoisky has also controlled the management of the state-owned oil pipeline company Ukrtatnafta. Oil has presumably been Kolomoisky’s main source of revenue for the last decade.

These practices were as blatant as they were unacceptable, and the question was whether the Ukrainian state had sufficient strength to stop them. The answer came March 19-25. The oil “auctions” became real auctions with normal market prices. The Rada adopted a law on normal corporate governance in joint stock companies, tentatively depriving Kolomoisky of control of Ukrnafta. Poroshenko sacked Kolomoisky’s loyalist as the head of Ukrtatnafta. He crowned his attack by sacking Kolomoisky as governor of Dnipropetrovsk.

Admittedly, Poroshenko tried to patch up his relations with Kolomoisky after this attack, but the balance of forces had changed. The president, Parliament and the government had imposed their authority, and they had done so with the help of journalists and civil activists in Parliament. In the future, Ukrnafta’s oil is likely to be sold on a normal market.

Vadim Novinsky, a former Russian citizen turned Ukrainian lawmaker and businessman, speaks to customers of his Forum Bank on March 28, 2014 , three months before the central bank closed it down

Vadim Novinsky, a former Russian citizen turned Ukrainian lawmaker and businessman, speaks to customers of his Forum Bank on March 28, 2014 , three months before the central bank closed it down

How to proceed

Ukraine needs successful businesspeople. Policy should focus on leveling the playing field, not on punishing success.

In 1998, the leading gas trader Ihor Bakai famously stated that all rich people in Ukraine had made their money on trading gas. The business model was simple: borrow ample and cheap credits from Gazprombank; buy gas from Gazprom at a privileged price; establish a monopoly of gas sales in Ukraine. On April 1, the government raised the household price to half the market price, taking away most of the possibilities of privileged arbitrage. The prices have to reach market level, which will be easier with lower international gas prices. The Verkhovna Rada has already adopted a law on a normal gas market in Ukraine, which will hurt Firtash’s monopolistic business. Finally, Ukraine should stop trading gas with Russia, since Russia’s main purpose is to corrupt Ukraine, which the current Naftogaz leaders try to stop. The liberalization of energy markets is the most important measure against corruption.

Similarly, the government is attempting to impose normal management on valuable state corporations and sell off the state enterprises that do not really work so that their assets can be utilized. The government has already carried out a lot of deregulation and abolished many inspection agencies, but more is needed. The pervasively corrupt judicial system has favored the most dubious businesspeople, which is why the adopted law on lustration needs to be fully implemented and not stalled. Similarly, all kinds of enterprise subsidies should be abolished. The abolition of coal subsidies is an excellent step, but the opaque budget undoubtedly hides many other enterprise subsidies that need to be revealed and eliminated.

A political problem

We should look upon oligarchy as a political problem. Oligarchs do not make their money on the market but on privileges granted by government connections. Lustration and a new constitution will hopefully take care of the judicial system and law enforcement. Ukraine’s oligarchs still dominate TV, but that industry is suffering large losses. Thanks to the Internet and social media, pluralism is great. Many new ministers are clearly not corrupt. Ukraine benefits from a very active civil society.

A remaining problem is Parliament. From 2002 until last year, it had an oligarchic majority. Thanks to the October elections, 56 percent of the current deputies are new and have never been parliamentarians before, which vouches for a certain decency.

Yuriy Kosyuk, owner of the country’s largest poultry producer MHP, and one of the largest farming enterprises, gives an order at his office in Kyiv on June 12, 2013.

Yuriy Kosyuk, owner of the country’s largest poultry producer MHP, and one of the largest farming enterprises, gives an order at his office in Kyiv on June 12, 2013.

Three prominent oligarchic groups remain apparent.

The Firtash-Lyovochkin group has 40-50 deputies (25 in the Opposition Bloc and some in the Poroshenko Bloc), Kolomoisky about 20 and Akhmetov 15 (in the Opposition Bloc). Akhmetov peaked at 90 deputies; only the Firtash-Lyovochkin group maintains its prior strength. As a consequence, good reform legislation is adopted with about 275 votes.

Yet, electoral reforms could improve the situation. Most business lobbyists in the Rada are elected in one-person constituencies. If Ukraine introduced purely proportional elections, most of them could be ousted and the parties strengthened. The cost of elections would be reduced and wealthy businesspeople deprived of their advantages if all political TV advertisement were prohibited and only state financing of campaigns was allowed.

Ukraine’s political institutions currently are strong enough to defeat the oligarchic system. The coalition partners are happy to expose one another’s wrongdoing. Several new ministers are insightful, brave and forceful. A few young journalists and activists in parliament, such as Serhiy Leshchenko, Hanna Hopko and Mustafa Nayem, have exposed one scandal after the other.

This is an important process, but it has to continue before the old elites recover.

Anders Aslund is the author of “Ukraine: What Went Wrong and How to Fix It.”