Ukraine’s path to prosperity runs right through Volodymyr Omelyan’s ministry.

The infrastructure minister oversees more than 1 million people, or 5 percent of the nation’s active workforce. His portfolio includes railways, roads, ports, air traffic and postal service.

Omelyan brings libertarian views and transparency to the job he took over on April 14, 2016 from Andriy Pivovarsky, whom he served as deputy minister. His task is formidable — to revamp a Soviet-style ministry with a sordid history of corruption.

His direct team of 250 state employees includes a large number paid by the European Commission and other donors. He tries to give them a free hand to do their jobs.

“I always delegate power to people we select and appoint,” Omelyan told the Kyiv Post in a Feb. 12 interview. “It’s very counterproductive if I hire a CEO… and then tell them what to do on a daily basis.”

Omelyan also wants to let the private sector take control of more of Ukraine’s infrastructure to encourage competition and better performance.

The 39-year-old Omelyan is a lightning rod for criticism from vested interests that have benefited from the ministry’s corrupt schemes. His approach is a far cry from the secretive ministers who had been the norm for much of independent Ukraine’s history. He has started weekly briefings with the media.

This approach helps keep everyone accountable, he says. “My publicity is also a good controlling measure for myself. If I say it publicly I should do it.”

Critics

Omelyan believes he is the right person for the job, even though most of his experience has been in foreign affairs, and not infrastructure or the private sector.

Some have described Omelyan as a protégé of Ukraine’s Prime Minister Volodymyr Groysman. However, the minister says that the only paycheck he receives is from the Infrastructure Ministry, and denies having any personal business contacts with oligarchs or politicians.

“I’m happy that I have never compromised my integrity or done anything bad to my country,” Omelyan says.

His predecessor, Pivovarsky, resigned in December 2015, citing Ukraine’s refusal to prosecute high officials for corruption. Omelyan sees himself as picking up where Pivovarsky left off, and says that he still speaks with his former boss occasionally.

Asked whether he was willing to give the names of corrupt players in the field, Omelyan says that he tried it before and it didn’t help. He was silenced by legal action. “I lost in all the courts. I can’t name them again,” he says.

In November 2017, Omelyan wrote on his Facebook page that former Ukrzaliznytsia director Mikhail Kostyuk, lawmaker Yaroslav Dubnevych and his brother Bohdan, as well as Ukrzaliznytsia manager Serhiy Myhalchuk, were all suspected of theft, and that prosecutors and police were investigating.

Ports

But speaking out led to action in at least one case. Andriy Amelin, the former CEO of Ukrainian Sea Ports Authority, a state enterprise that oversees tenders and collects revenue, was arrested and is now being investigated by the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine for profiteering from shady tenders.

“I hope that he is only the first one who is arrested in the infrastructure sector,” the minister says.

Amelin’s replacement with Raivis Veckagans was a big victory for Omelyan in the maritime sector. Improvements are already happening. Recent deals with DP World and Hutchison Ports are just the beginning, with many more to come, he says.

Other projects, such as dredging the Yuzniy and Chornomorsk sea ports, show that investors and businesses are interested in revitalizing shipping.But the minister says parliament still has to approve the privatization of ports and other state assets for major changes to take place. “I hope that this will be a top priority for the president and prime minister,” Omelyan says.

Another victory is the establishment of the Maritime Administration, a single state body to oversee Ukraine’s international maritime obligations and sea security issues. “It’s a great success,” the minister says, replacing chaotic regulation among numerous agencies.

The government has lowered sea port duties and taxes by 20 percent. But Ukraine’s ports still remain among the most expensive.

Additionally, because of ecology inspectors’ demands for bribes, inspections are now recorded on video.

“Right now, it’s an issue for the Ecology Ministry, but we are cooperating with them fruitfully just not to let crooks make illegal actions,” he says. “It’s ridiculous when foreign vessels, as well as Ukrainian vessels, enter a Ukrainian sea port and are met by a bunch of unknown guys demanding money.”

Roads

Omelyan is most proud of reforms in the road sector.

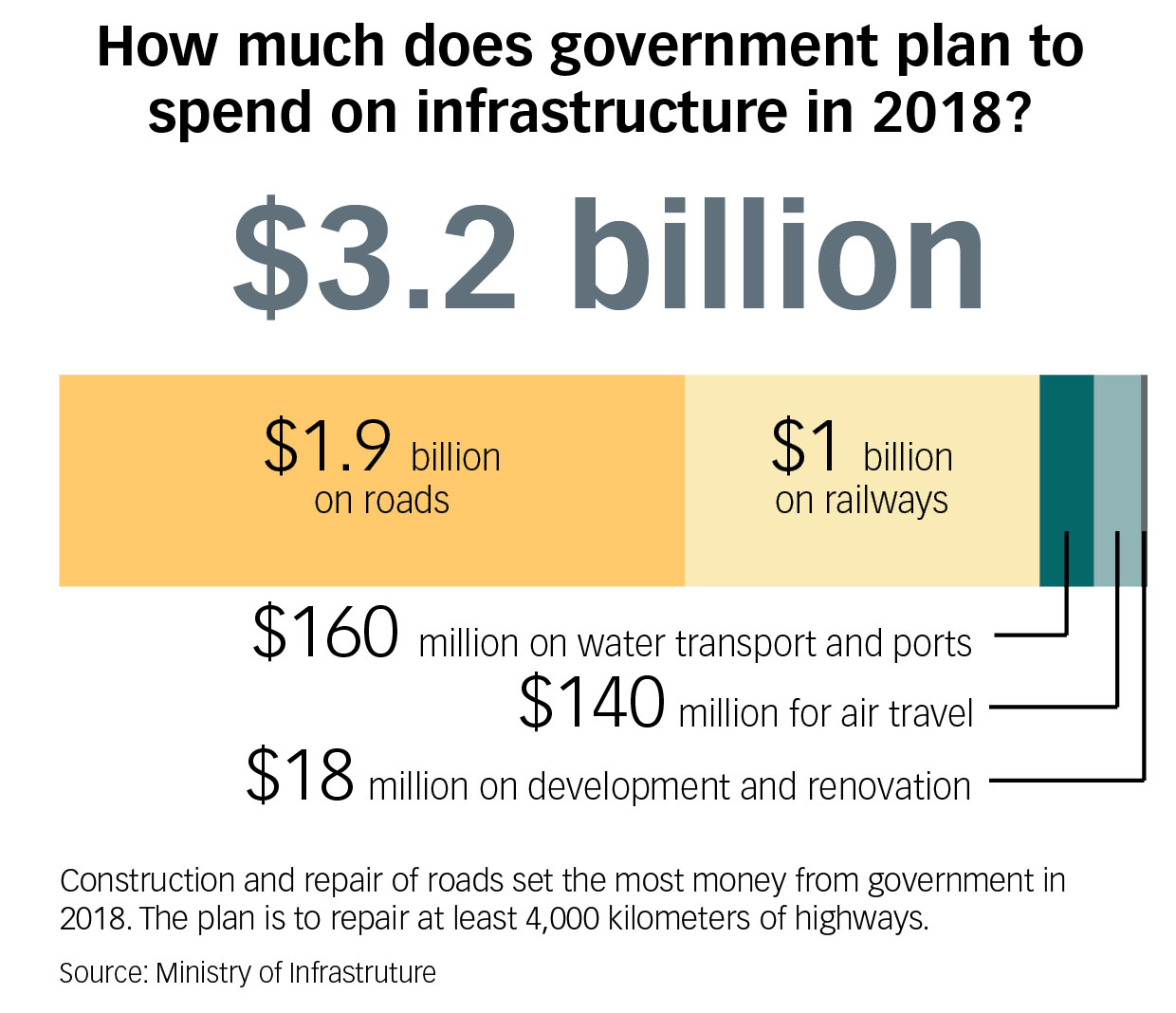

The state has allocated $1.8 billion to upgrading road infrastructure this year, including for road safety and digitalization measures.

“Two years ago, it would have been a dream to have at least Hr 1 billion for road repairs,” he says. This year, the minister expects to upgrade 4,000 kilometers of roads in a campaign much heralded by Prime Minister Groysman.

With new road infrastructure, Ukraine will be able to boost its annual gross domestic product by another 3–4 percent, the minister says.

The ministry also established a State Roads Fund that went into force on Jan. 1. This will make it easier to attract investors and to build concession roads.

Most of the success comes from the new administration at Ukravtodor, Ukraine’s state roads agency, which is now run by Slawomir Novak, Poland’s former infrastructure minister.

Ukravtodor is also being decentralized: now it is responsible only for 47,000 kilometers of major highways. The other 70 percent of the road network is now to be managed at the regional and municipal levels.

The ministry has brought in two independent organizations to oversee road construction. One is the Construction Sector Transparency Initiative, established with the help of the British government and United Nations.

“They check everything connected with road reconstruction, starting from the tender procedures and ending with the completion of the roads,” Omelyan says.

The second is the International Federation of Consulting Engineers, or FIDIC, an internationally recognized association of independent engineers. Each company that wins a tender should hire a FIDIC engineer that oversees the construction and takes responsibility for road quality. In addition, each road work is now supposed to be guaranteed by a warranty of at least five years.

Before, the minister said, at least 50 percent — billions of dollars — of Ukraine’s road budget was simply stolen through various schemes such as signing a contract for a three-layered road, when actually only a one-layer one was built.

“This is also an explanation of why Ukraine’s roads are of such poor quality,” he says. “Because on paper you invest a lot, but in reality there’s a huge difference.”

Buses

Another form of corruption in Ukraine involves bus routes. Today the market is still underdeveloped, provides poor service and is dominated by Bohdan Motors Corporation, shares of which used to belong to Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko.

“It was a corrupt scheme. The only people who had close connections to the local authorities or to government bodies were allowed to open new bus routes or new bus destinations,” Omelyan says.

But that is now changing. Now companies can compete to operate new bus routes, the minister says.

Airlines

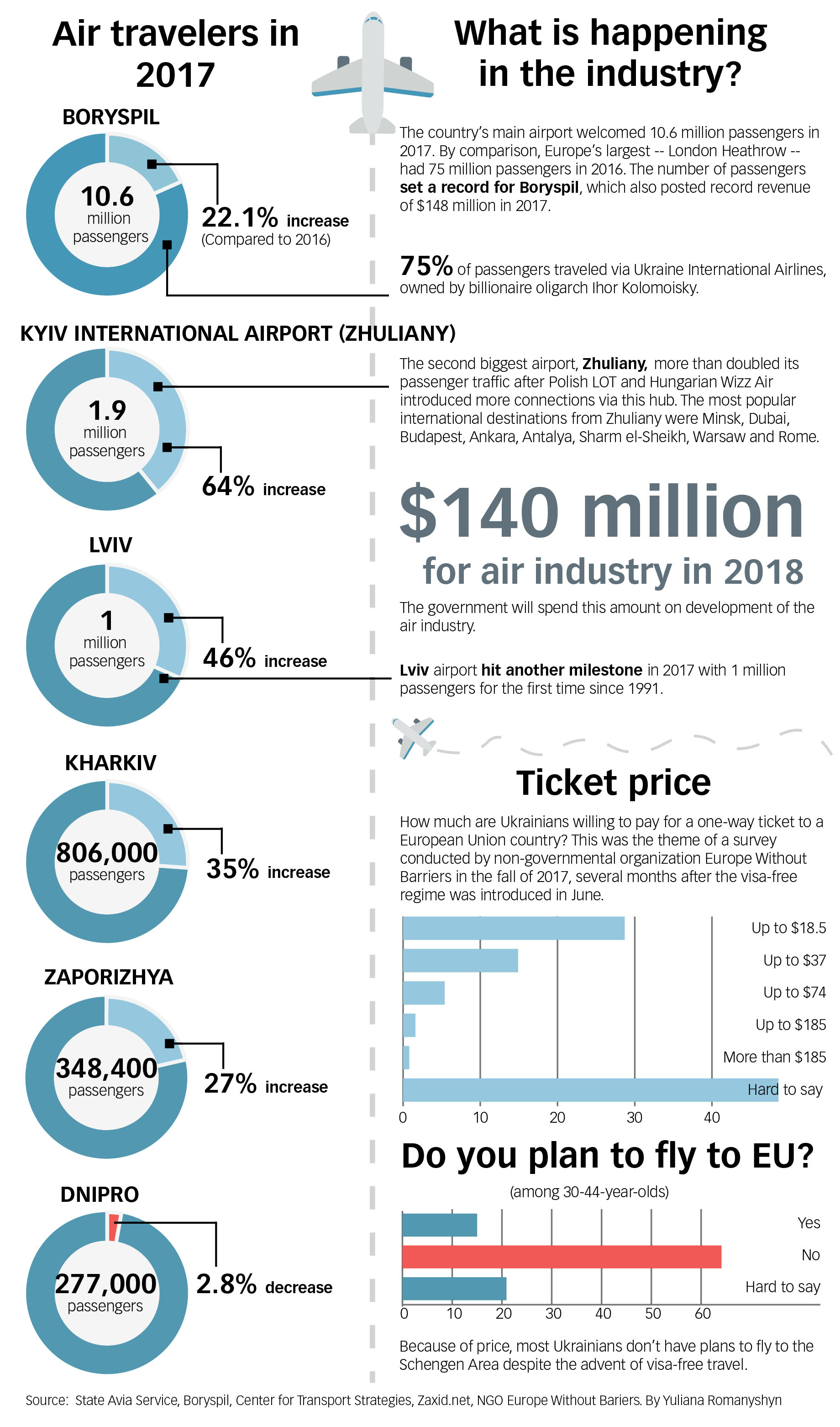

Another monopoly is in the skies. Ukraine International Airlines, owned by billionaire oligarch Igor Kolomoisky, controls more than 50 percent of the market, the minister says.

“There was huge resistance in 2017 from (Kolomoisky’s) company, and that’s why the first try to get RyanAir to enter the country was not successful.”

Omelyan’s plan was to have the Irish low-cost carrier in Ukraine by September 2017. But plans fell through when the airline and the airports could not agree on terms. But the minister is still not giving up, and he is confident that this year will be the year of low-cost airlines for Ukraine.

He expects RyanAir to enter during the fall, together with Spanish low-cost Vueling and another European market player which Omelyan didn’t want to name.

It’s a start in getting Ukraine International Airlines used to the idea of competition.

“All of them, even Ukraine International Airlines, recognize that yes, low-cost carriers will enter the market, and we should be ready for it.”

Kolomoisky’s willingness to compromise may have been motivated by a United Kingdom court’s freeze on $2.5 billion of his assets. “Yes, that definitely played a part,” Omelyan says.

Kolomoisky’s control is weakening in other areas.

Denys Antoniuk, viewed as working on Kolomoisky’s orders, was dismissed from the State Aviation Service, which regulates airline routes. “Everything positive that is happening right now is thanks to the transparent position of the State Aviation Service,” Omelyan says.

Boryspil International Airport CEO Pavlo Ryabikin is also more independent from Ukraine International Airlines than his predecessors, the minister says. The results: Record air traffic and record revenue in 2017.

Omelyan is more optimistic about Lviv Danylo Halytskyi International Airport after Tetyana Romanovska took over its management.

“In 2015 we were about to close Lviv airport,” he says. But 2017 was a record year, with more than 1 million passengers.

Other airports on the minister’s radar are Dnipro and Odesa international airports.

Railways

One sore point for the minister is Ukraine’s state-owned railways monopoly Ukrzaliznytsia, historically a cash cow for vested interests. And although Ukrzaliznytsia has been making progress, including reaching profitability last year, Omelyan says that it can do much more.

“This company could be… the number one company in Ukraine,” he said, describing himself as “unhappy with the situation.”

Omelyan had a public dispute last year with the monopoly’s former CEO, Wojciech Balczun, who was criticized by Omelyan for inaction until his August 2017 resignation. During the dispute, the Cabinet of Ministers took control of the monopoly.

Despite the problems, Omelyan hopes for new projects, including a high-speed Odesa-Kyiv-Lviv route that would cost an estimated $1 billion. It’s not clear where the money for that project will come from.

Ukraine also struck a deal with U.S. company General Electric on Feb. 14 to produce locomotives in Ukraine to better meet cargo demands and ease last year’s “huge bottleneck” for exporters. The official signing ceremony will take place on Feb. 23.

This year Ukrzaliznytsia plans to invest about $1 billion in its rail fleet. This includes purchasing 60 new wagons, 30 General Electric locomotives, the production of 3,600 freight wagons, and the modernization of 226 passenger wagons and 10,000 freight wagons.

Postal service

Ukraine’s state-owned postal service UkrPoshta is also rebounding. The state-owned enterprise, another source of corruption in Ukraine, is led by new CEO Ihor Smeliansky.

Companies often bribed the postal service to transport goods for free. Today that has stopped, says the minister.

“There is no shadow deal possible with Smeliansky,” Omelyan says. “I don’t have any problems with his integrity.”

UkrPoshta has been forced to change with the rise of private players such as Nova Poshta and is now cooperating with U.S. company Amazon and China’s Alibaba.

“Soon you will hear of another huge project by UkrPoshta and another state company,” Omelyan promises.